water works (ongoing)

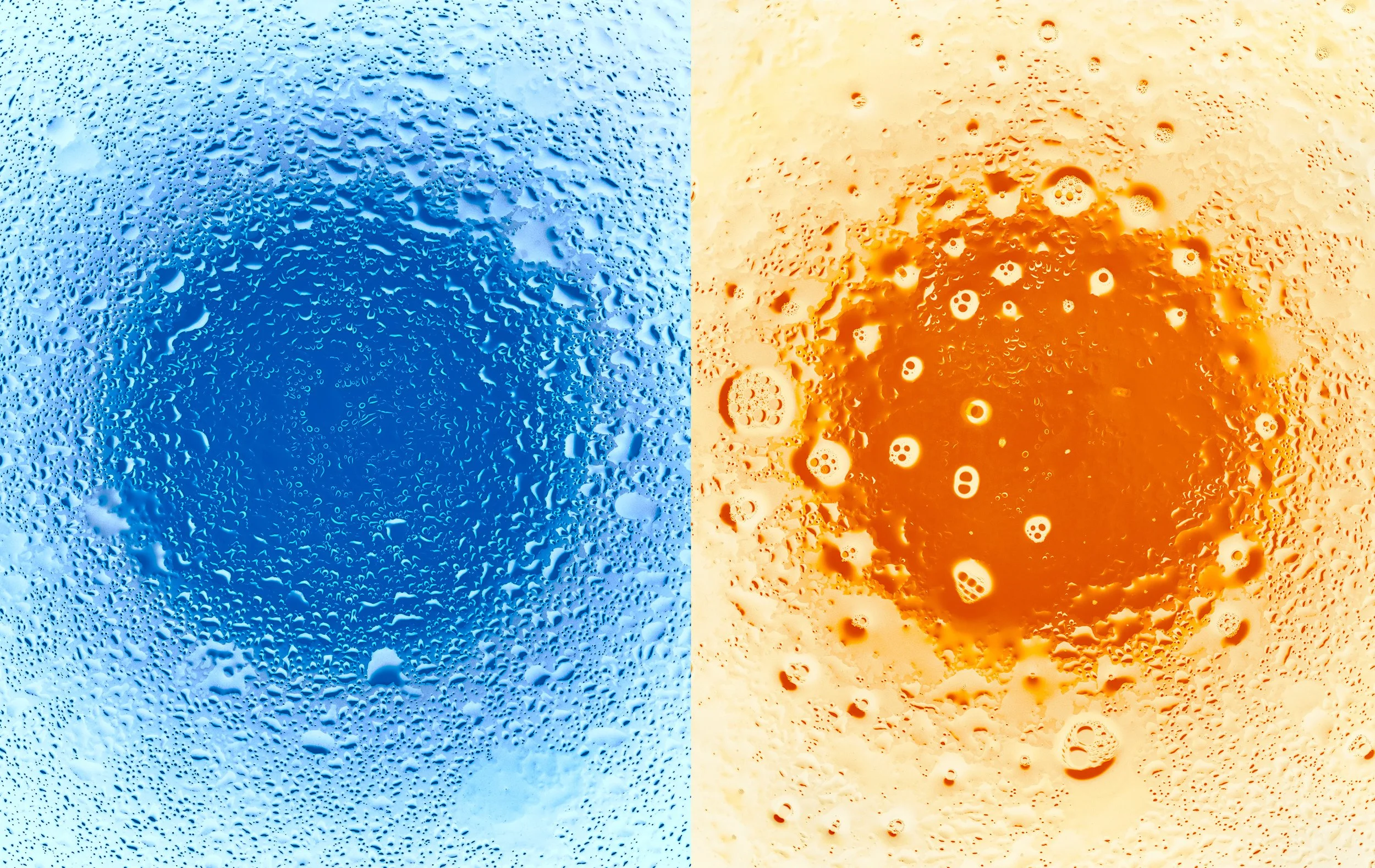

1. Water Works is an ongoing project with no pre-determined path forward or a clear idea of its final resolution. The project places importance on the process (presence) over the outcome (future). It considers how I might work with fewer images while identifying more uses for the images I produce as an ecological aware action.

2. Originally, these two images for Water Works were made for the exhibition Utopian Tongues, curated by Jake Treacy, at Seventh Gallery, Melbourne, Australia, in 2018. The exhibition provided artists with a platform to consider how art might act as a conduit for ‘potent change, transformation and healing.’

3. An entry point to making these images was the following text by Hong Kong–US martial artist Bruce Lee (1940–1973).

Empty your mind.

Be formless, shapeless, like water.

You put water into a cup, it becomes the cup.

You put water into a bottle, it becomes the bottle.

You put it into a teapot, it becomes the teapot.

Now water can flow or it can crash.

Be water, my friend.

4. At the time of making these images, I was living in the Central Province of Papua New Guinea with my Bougainville husband. I was situated in a new culture and society which demanded flexibility and adaptability due to the unpredictable nature of everyday life of living in Papua New Guinea.

Lee’s philosophical analogy to water as a receptive, malleable entity stripped of ego and preconceptions became a valuable metaphor for me to negotiate life in Papua New Guinea. Particularly how Lee invites us to adapt to arising situations and flow around and absorb obstacles rather than crash against them. Stagnant water ceases to breathe, while flow becomes analogous to progress and personal growth.

Being embedded in the Papua New Guinean society also required me to have greater practicality and use my skills for many purposes (as opposed to being a specialist) to produce multiple effective outcomes. Furthermore, access to many things (household goods, services, or even art practices) was limited, and we continually made do with what was available to us at the time.

This way of living (and thinking) profoundly affected how I make my images function, both aesthetically and in practical terms.

5. Images have been presented as part of the Bakehouse Studio Billboards Project for the Centre for Contemporary Photography in 2019 and for the Picture Windows commission for the City Of Melbourne Council in 2020. In both instances, the images were simply rotated to work with the billboard perspective (prioritising image function over original aesthetic choices). I made one of the images into a short video for a one-night gathering for Telos in Melbourne in 2021. Another image was printed onto paper and had embroidered text embedded into the surface for the exhibition Ecologies of Change in 2021. Curated by Clare Humphries (Australia), Jacki Baxter (UK) and Venessa Pugh (UK), this project brought together artists ‘who share an ethics of care for Earth's ecosystems.’

At present, these works have been printed onto fabric, and I have embroidered text on them. I am thinking of utilising these pieces of fabric to make a quilt for my baby.

kukarei inakarei / knowledge continuum, 2018

Kukarei inakarei / knowledge continuum is a final part of the long-term project that depicts the medicinal plants of the Siwai region of Bougainville Island, an autonomous region of Papua New Guinea. The project stems from Chief Alex Dawia, Taa Lupumoiku Clan, and Chief Jeffrey Noro, Rura Clan, concerns that tacit oral knowledge systems are eroding due to external influences. They saw that one way to preserve this vital cultural knowledge was to codify it through images and text for current and future local generations.

The twelve-metre long fabric panel rests over a wooden rod and gathers onto the floor on each side to visually convey how knowledge overlaps, fades, and repeat. Fabrics, much like images, saturate our daily lives. However, fabric shares an intimate relationship with our bodies night and day. Through the intertwining of fibres, the fabric’s texture and weight provide protection. Combining the analogue lumen process and digital scanography process creates the plant images on the fabric. It becomes a way to embody the critical changes in community knowledge systems and the photographic language.

This artwork not only provides knowledge preservation. It also reveals a community’s desire to connect to a global society for mutual understanding of how their knowledge is inseparable from the natural environment. At the community’s request, medicinal plant uses and applications are hand-embroidered in English to accompany each plant’s traditional name on the fabric panel. With more than two hundred hours of embroidery labour by the artist and her mother, the artwork embodies more than one way of being and knowing for a shared future.

Kukarei inakarei / knowledge continuum, 2018, digital prints on organic cotton fabric with hand-embroidered thread, 1200 x 125 cm (image credits: Matthew Stanton).

kuna siuwai pokong, 2018

Kuna Siuwai Pokong details over thirty traditional medicinal plants with their healing properties and cultural values from the Siwai region of Bougainville. Bougainville Island is an autonomous region of Papua New Guinea.

The project stems from Chief Alex Dawia, Taa Lupumoiku Clan, and Chief Jeffrey Noro, Rura Clan, concerns that tacit oral knowledge systems are eroding due to external influences. One way to preserve this vital cultural knowledge is to codify it within a book format for current and future generations. The book prioritises local Motuna language throughout since language and plant knowledge are inextricably linked in the Siwai culture. The book aligns with the cultural need for art in Bougainville to be practical and functional.

The book is an outcome of a cross-cultural project with Australian photographer Kate Robertson. The book is published by The Kainake Project, a community-based grassroots organisation in Bougainville. The Kainake Project promotes the use of traditional leadership structures and cultural and traditional knowledge for locals to conserve their environment sustainably.

Books have been handed to schools throughout Siwai, and a portion is available for purchase internationally, with all money supporting community projects. Book sale proceeds have already purchased a water tank for the Kainake Village. Books were also given to community-based grassroots organisation Rara-Rarei Foundation Inc. to use as a fundraising tool for their continued efforts to build libraries and train librarians across Siwai.

The UNDP funded the printing of the book through its Small Grants Program.

Kuna Siuwai Pokong can be purchased by emailing info@kainakeproject.org.

Book details

500 copies

80 pages

21 x 15 cm

Motuna and English

ISBN: 978-0-646-99227-3

published in 2018

Press

Papua New Guinea Post Courier

Loop PNG

TVWAN News (Papua New Guinean TV channel)

Collections

Australian Museum (AUS)

Field Museum (USA)

Papua New Guinea National Museum and Art Gallery (PNG)

recording the medicinal plants of Siwai, Bougainville, 2016

Recording the Medicinal Plants of Siwai, Bougainville stems from an invitation to create photographic light recordings of traditional medicinal plants within dense rainforests in the Siwai region of Bougainville Island, an autonomous region of Papua New Guinea.

Concerned with the erosion of tacit traditional medicinal knowledge, Chief Alex Dawia of the Taa Lupumoiku Clan approached Kate to use photography to chronicle Siwai plant knowledge for preservation. Although not from his culture, community or region, Chief Dawia felt that they were connected in mutual interests of self-transcendence—a connection he had made when viewing the series Dust Landscapes in Melbourne.

Chief Jeffrey Noro of the Rura Clan, also from Siwai, joined their efforts, motivated by similar concerns to preserve tacit knowledge systems. Chief Noro also lived through Bougainville’s civil war (locally known as the Crisis) from 1989 to 1997 and had desired to provide positive community outcomes after such a traumatic period in Bougainville’s history.

The lumen printing process, which uses expired colour or black and white light-sensitive photographic paper, was chosen because it could be undertaken onsite in Siwai and offered direct community engagement with the photographic process. As an action exhibiting ecological awareness, the expired photographic paper is also upcycled and offered another life.

Community members gathered plant materials and brought them to the makeshift studio space, which also housed local meetings. Over a few hours, the sunlight and humidity slowly orchestrated an imprint onto the substrate by activating and enmeshing the chemicals in the photosensitive paper with those of the plant matter. In the nearby rainforest, used plant material was discarded to decompose and regenerate the forest. In their latent state, the resulting lumen prints were packed away in a light-tight black bag for transportation to Melbourne.

Back in the studio in Melbourne, the lumen prints were translated into digital data through the scanography process. While the analogue lumen print remained vulnerable to light, leading to an opaque demise each time exposed to the flatbed scanner’s light, the digital process immortalised the image through its capturing method that occurred over time and space under the scanner's glass pane. Movement of the lumen print while scanning created glitching, as well as unconventional and broken image edges that referenced distortions in tacit knowledge dissemination from one generation to the next.

Conventional presentation of photographic prints on the white walls of the gallery was rejected in favour of tabletop presentation (under INSTALL DOCUMENTATION on this website) to mirror the way community members engaged with the production of the lumen prints at Kainake Village.

Latin scientific plant names for the artwork titles were rejected in favour of local Motuna language plant names. This was particularly important, given that traditional language and the environment are inextricably enmeshed in Siwai: ‘When you lose the traditional name, you lose the knowledge of the plant because the traditional name of the plant describes the functionality of the plant’ (The Kainake Project 2018). The final images are at a 1:1 ratio of the original plant material.

alchemy, 2017

For this commission, the four stages of alchemy (Nigredo, Albedo, Citrinitas, and Rubedo) were conveyed to represent the process of connecting the self, through the meeting and aligning of the unconscious and the conscious. Alchemy reflects the process of personal transformation in the metaphor of transmuting base metals into gold. This process of individuation was explored through reflection on experiences with the individuation process, and the writings of Carl Jung in the book Psychology and Alchemy (1968).

The photographs are a combination of layering multiple analogue and digital photographic processes and techniques, including darkroom printing, photograms, chemigrams, scanograms, digital manipulation and large format camera re-photographing techniques in the studio.

The resulting eight artworks were utilised for website identity, framed artworks, and room key cards.

Clients

Fabio Ongarato Design & Jackalope Hotel on the Mornington Peninsula.

cosmic walk and other learnings

The Cosmic Walk and Other Learnings explores experiential learning and focuses on understanding the deep ecology environmental philosophy. Deep ecology observes that psychological and spiritual disarray can be attributed to the ‘illusion of separation’ between humans and the rest of the natural world. This concept is seen as a fundamental underlying issue of the current environmental crisis.

From the experiences of attending numerous deep ecology workshops, a series of photograms were developed to convey the sensory modes of understanding inherent in the workshop processes and practices.

Workshop tools and concepts such as string, leaves, dirt from the earth and the circle shape were utilised to create the photograms. The artwork titles are workshop names or healing concepts, such as The Cosmic Walk, Circle Work and Breathing with Trees.

celestial body model

Celestial Body Model explores the potential to photographically convey intangible experiences emanating from practical processes or physical activities within deep ecology. Deep ecology is an environmental philosophy that observes how psychological and spiritual disarray can be attributed to the ‘illusion of separation’ between humans and the rest of the natural world.

Several deep ecology workshops were attended and engaged in for over a year. For this body of work, the activity Earth as Peppercorn was re-presented in photographic forms. This activity invites workshop participants to slowly walk through a scale model of the solar system to experience its vastness of space compared to planet proportions. Readily available items such as melons, pins and chickpeas were used in the activity and photographic images as representations for each planet.

These works employ different photographic techniques to greatly slow down and extend the photographic process of making an image, including numerous iterations of re-photographic techniques, hand printing in the darkroom and hand toning. Creating these images took over six months and reflected deep ecology themes of connectedness, observation and mindfulness to emphasise process over outcome.

dust landscapes, 2012

Dust Landscapes depicts dust collected from ConFest, a festival held by an alternative healing and spiritual community in the dry landscape of southwest New South Wales, Australia.

Throughout the festival, as participants move around the site, the land is unsettled, and clouds of dust are created that linger listlessly above the ground. The wind stirs the dust particles across the ConFest site, clinging onto festival-goers as they immerse themselves in community rituals and spontaneous happenings.

Extracted dust particles from the site were brought back into the studio and photographed through various processes to create unfamiliar topographical maps. The dust particles act as artifacts of the ‘celestial experience’ of ConFest, mapping the festival’s disorientating, surrendering, transformative and energising qualities.